In these turbulent days, when the leaders of the world have to deal with everything from war to disease, it is easy to overlook the importance of our soil.

But, as the Romans discovered, poor soil can damage or even destroy empires.

In America, the Dust Bowl was a stark reminder of what can happen in modern times – damaging farmland, displacing families, and crippling the economy. The crisis was so bad, it led Roosevelt to warn that:

“The nation that destroys its soil destroys itself.”

But there was a time when America’s leaders were much closer to the soil.

They carried out composting experiments, issued warnings about the dangers of poor farming practice – and finally led efforts to restore it when those warnings were ignored.

And it all started with the United States’ first president – George Washington.

George Washington: Compost Pioneer

You’ll no doubt know Washington as a wartime leader, a statesman, and a founding father.

But when not at war, George Washington could be found experimenting with boosting soil health or finding his escape in the pages of The Practical Farmer.

Washington started as a tobacco farmer, but his land was cursed with heavy clay and poor topsoil. He soon realized that tobacco plants were stripping his land of fertility, and approached the problem with a dual strategy (1):

“my object is to recover the fields from the exhausted state into which they have fallen, by oppressive crops, and to restore them (if possible by any means in my power) to health & vigour.

“But two ways will enable me to accomplish this. The first is to cover them with as much manure as possible (winter & summer). The 2d a judicious succession of Crops.” (2)

In fact, Washington’s concern with fertility turned into an almost obsessive interest with manure, with the President writing that a good farm manager must be:

“Midas-like, one who can convert everything he touches into manure, as the first transmutation towards Gold” (3).

He made experiments with both green manure and animal manure, and mixed ten different compost materials, including dung from various animals, river mud, marl (a lime-rich clay), and clay, before testing seeds in each one to see which performed best (4).

17 years later his commitment to improving his soil led him to build a dedicated “dung repository” to turn manure into usable fertilizer.

This building had serious scale, being 31 feet long and 12 ½ feet wide, with a brick foundation, a recessed floor, and open air to aid ventilation.

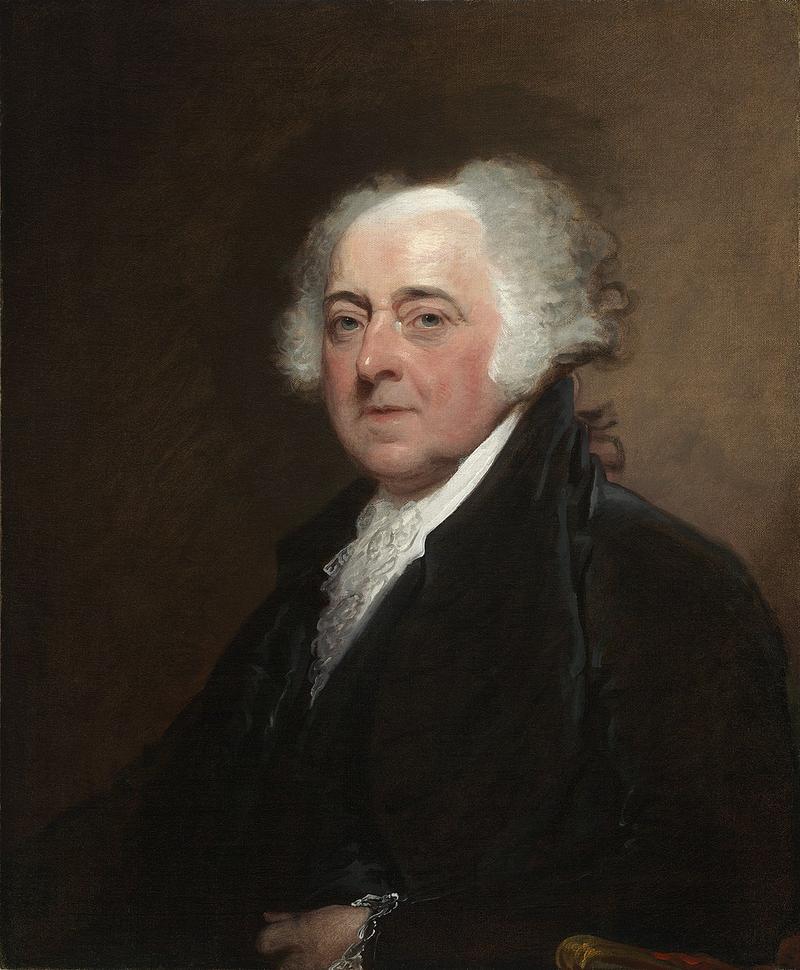

John Adams: Gentleman Farmer, Manure Advocate

Washington wasn’t alone in his composting pursuits—his successor, John Adams, was also a strong advocate for fertility, with a particularly keen interest in manure.

Complaining about one garden he visited, he wrote:

…it is full of flowers and of roots and vegetables of all kinds, and of fruits; grapes of several sorts, and of excellent quality, pears, peaches, &c.; but everything suffers for want of manure. (5)

On the other hand, he was full of praise for the manure in the UK, even if it didn’t match those on his own land:

There are, on the side of the way, several heaps of manure, a hundred loads perhaps in each heap. I have carefully examined them, and find them composed of straw, and dung from the stables and streets of London; mud, clay, or marl, dug out of the ditch along the hedges; and turf, sward, cut up with spades, hoes, and shovels, in the road. This is laid in vast heaps, to mix …

This may be good manure, but is not equal to mine, which I composed in similar heaps upon my own farm. (6)

He also wrote in detail about his own composting experiments – which included seaweed, now known to be a valuable source of nutrients that stimulate plant growth:

“Wednesday. B. and S. making and liming a heap of manure. They compounded it of earth carted in from the ground opposite the garden, where the ha-ha wall is to be built, of salt hay and seaweed trodden by the cattle in the yard, of horsedung from the stable, and of cowdung left by the cows. Over all this composition they now and then sprinkle a layer of lime” (7).

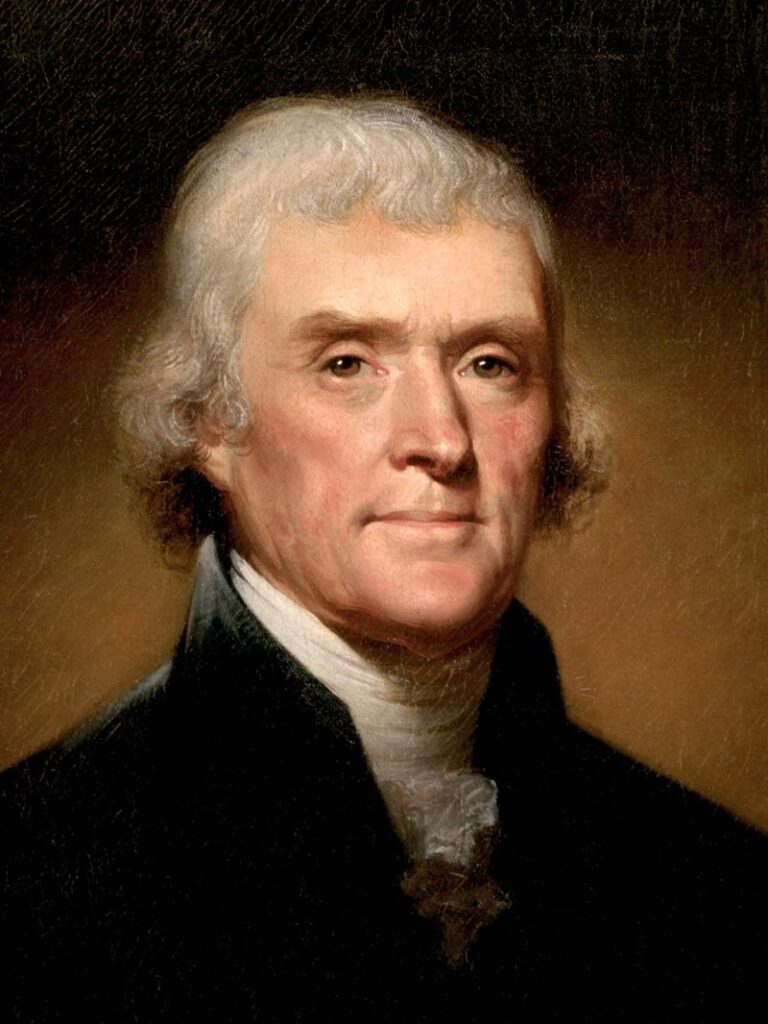

Thomas Jefferson: The Experimental Farmer

Thomas Jefferson shared Washington’s and Adams’ appreciation of manure – and overtook them when it came to carrying out experiments!

In fact, his neighbors jokingly called him “the worst farmer in Virginia” due to the number of experiments that failed.

But those experiments helped Jefferson grow to understand his land and soil, and led him to applying an advanced seven-year crop rotation to help the ground recover between cash crops.

These crops included some which are still used today to improve soil, such as vetch and clover.

In these days before insecticides, he also understood that manure was crucial to soil and plant health. When his daughter’s garden suffered from insect damage, he wrote to her:

“We will try this winter to cover our garden with a heavy coat of manure.

“When earth is rich it bids defiance to droughts, yields in abundance and of the best quality. I suspect that the insects which have harassed you have been encouraged by the feebleness of your plants, and that has been produced by the lean state of the soil.—We will attack them another year with joint efforts” (8).

James Madison: Soil Prophet

Like the other Presidents here, Madison had a keen appreciation of the value of manure and the need to husband it.

In his Madison address, he sounded like a modern organic farmer, saying:

“…that if everything grown on a soil is carried from it, it must become unproductive; that if everything grown on it be directly or indirectly restored to it, it would not cease to be productive” (9).

His speech was also prophetic, foreseeing the devastating damage that would occur if farmers neglected the soil.

Ultimately, those warnings would be ignored – with the US Soil Bureau writing in the 20th century that:

“The soil is the one indestructible, immutable asset that the nation possesses. It is the one resource that cannot be exhausted; that cannot be used up.” (10)

That careless attitude towards soil health would be costly – just a few decades later, the US suffered from the devastating Dust Bowl, a man-made ecological disaster that led to thousands of people leaving their homes.

And it would take another President to solve it.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: Honorary Mention

Roosevelt’s love was for trees rather than composting. In fact, when he recorded his profession at elections, it was “tree planter” rather than politician or President (11).

But his action to restore his nation’s soil means he deserves more than a mention in this article.

Roosevelt came to power in the devastating era of the American Dust Bowl.

Talking of it later, he said:

“I saw drought devastation in nine states.

“I talked with families who had lost their wheat crop, lost their corn crop, lost their livestock, lost the water in their well, lost their garden and come through to the end of the summer without one dollar of cash resources, facing a winter without feed or food—facing a planting season without seed to put in the ground.

“I shall never forget the fields of wheat so blasted by heat that they cannot be harvested. I shall never forget field after field of corn stunted, earless and stripped of leaves, for what the sun left the grasshoppers took. I saw brown pastures which would not keep a cow on fifty acres.” (12)

The Tree Planter’s understanding of soil would prove crucial to tackling the crisis.

Roosevelt established the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) to help farmers restore their land, acted to prevent overgrazing of soil, and oversaw the planting of 200 million trees as a windbreak to help prevent erosion.

It was considered one of the most successful environmental projects of our time (12).

Conclusion

America’s early leaders felt a strong connection to the soil. Far from hungering after political power, they keenly longed for the land and farming when they were kept from it by the vagaries of war and politics.

From crop rotation to replenishing the soil with organic matter, their experiments paved the way for insights that science would confirm centuries later.

James Madison, in particular, was a visionary, understanding the importance of soil long before it became widely recognized—and warning of the dangers of neglecting it. When those warnings were ignored, it took another president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, to address the resulting crisis.

The issues Madison foresaw and Roosevelt confronted remain just as relevant today. Across the world, soil degradation, the overuse of fertilizer, erosion, and climate change threaten our ability to produce healthy, sustainable food.

As we face a challenging future, we must ensure that today’s leaders—regardless of their backgrounds, nationality, or political views—recognize the health of our soil as the foundation of global prosperity.

Read more

Compost History: The Story of an Ancient Science: If you enjoyed learning about Washington’s “Dung Repository,” discover how ancient civilizations used similar methods to build empires.

23 Surprising Facts About Composting: From “hot” piles to the secret life of worms—everything you didn’t know about the biology of decay.

Sources

- City Farmer: George Washington, The Revolutionary Farmer: America’s First Composter. https://www.cityfarmer.org/washington.html

- Founders Online: From George Washington to William Pearce, 18 December 1793 https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-14-02-0356-0001

- The Historical Marker Database, Dung Repository https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=182581

- The Diaries of George Washington. Vol. 1. Donald Jackson, ed.; Dorothy Twohig, assoc. ed. The Papers of George Washington. Charlottesville The Diaries of GEORGE WASHINGTON Volume I 1748–65 https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/mss/mgw/mgwd/wd01/wd01.pdf

- Founders Online: Auteuil October 7. 1783. Tuesday. [from the Diary of John Adams] https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0002-0009-0002

- Massachusetts Historical Society, Diary of John Adams, volume 3 https://www.masshist.org/publications/adams-papers/index.php/volume/DJA03/pageid/DJA03p194

- Oll: The Works of John Adams, vol. 3 (Autobiography, Diary, Notes of a Debate in the Senate, Essays) https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/adams-the-works-of-john-adams-vol-3-autobiography-diary-notes-of-a-debate-in-the-senate-essays

- Encyclopedia Virginia: Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph (July 21, 1793) https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/letter-from-thomas-jefferson-to-martha-jefferson-randolph-july-21-1793/

- Founders Online, Address to the Agricultural Society of Albemarle, 12 May 1818, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/04-01-02-0244

- George Will, Herald Standard, Lessons learned from 1930s Dust Bowl “The soil is the one indestructible, immutable asset that the nation possesses. It is the one resource that cannot be exhausted.” https://www.heraldstandard.com/news/2007/may/03/lessons-learned-from-s-dust-bowlthe-soil-is-the-one-indestructible-immutable-asset-that-the-nation-possesses-it-is-the-one-resource-that-cannot-be-exhausted/

- National Park Service, Franklin D. Roosevelt: Tree Farmer, https://www.nps.gov/hofr/blogs/franklin-d-roosevelt-tree-farmer.htm

- Paul M. Sparrow, FDR Library., FDR and the Dust Bowl, https://fdr.blogs.archives.gov/2018/06/20/fdr-and-the-dust-bowl/

- Founders Online: From George Washington to William Pearce, 18 December 1793 https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-14-02-0356-0001